By Michael D. Briscoe

Colorado State University Pueblo

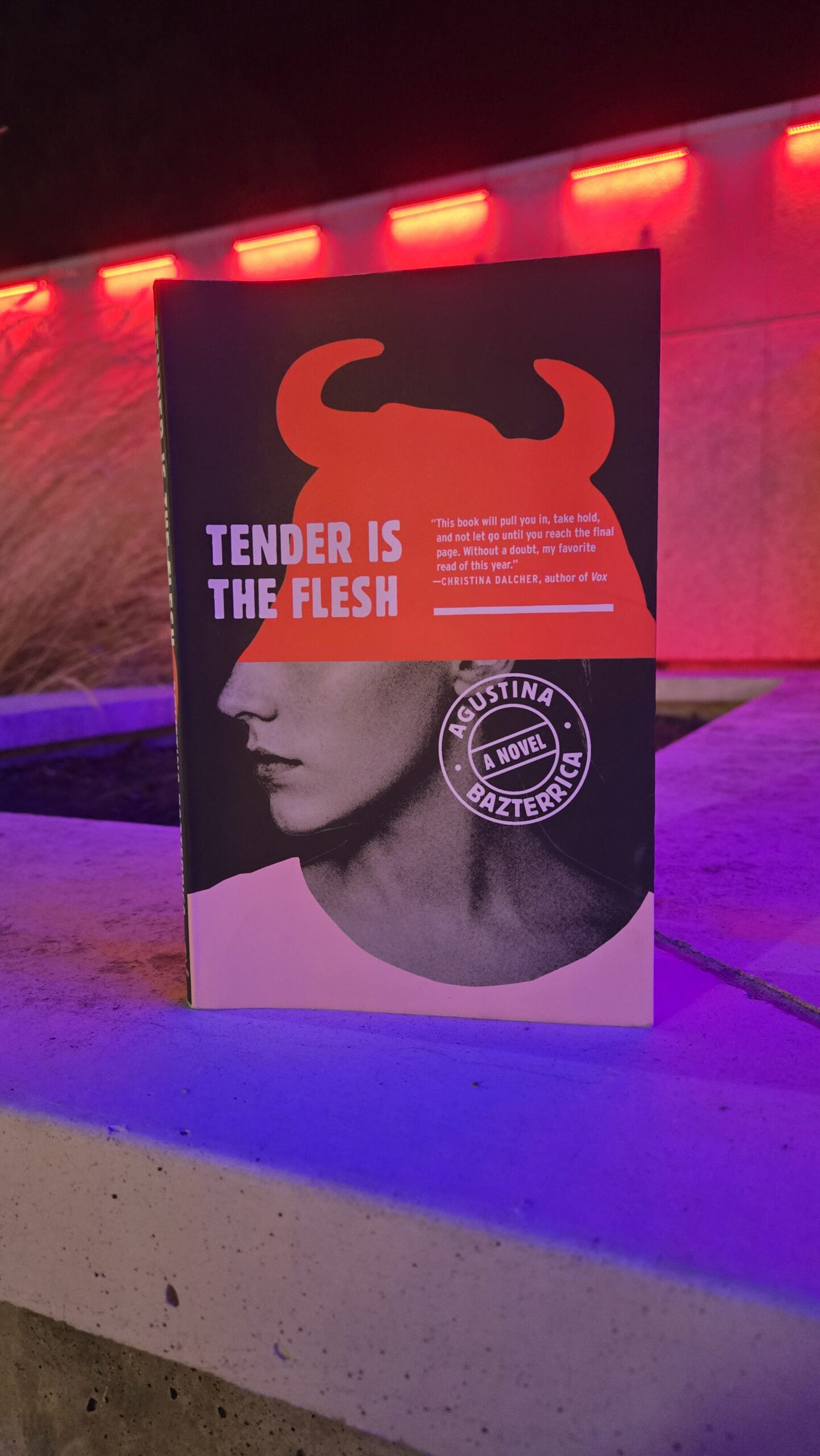

In my course, Crime and Society in Science Fiction, I have my students read the book Tender is the Flesh by author Agustina Bazterrica (2020). The book imagines a not-so-distant future in which humans can no longer eat animals. Not content with eating only plants, they turn to eating the flesh of other humans, which they refer to as “special meat.” It is filled with graphic descriptions of the torture and slaughter of humans raised for meat—essentially our own current animal industrial complex but with humans in place of animals. Without fail, students are disgusted at the practices.

After they’ve finished reading, I ask them a simple question, “should we eat humans?” The answer is inevitably no. I ask why, and they give answers about suffering, their families, fairness, how it isn’t necessary, etc. I then ask a similarly simple question, “should we eat animals?” The mood shifts. Suddenly, the easy answers no longer flow. I point out that all the reasons they themselves have given to not eat humans apply just as well to animals.

Faced with a logical contradiction in their ethics, the students realize this must be reconciled. Then, something unexpected happens. Rather than adjusting their view on eating animals to reconcile this contradiction, they begin to rationalize eating humans. The discussion often degrades as I point out that their rationales for eating humans are the same as the antagonists in the book and the same that have been used to justify human slavery, genocide, and other atrocities.

They shrug.

It is a profoundly frustrating experience. I know both as a teacher and sociologist that I can’t lead them directly to conclusions; they must arrive at them on their own by developing their sociological imagination, questioning the unquestioned, and making the familiar strange. At the same time, I recognize that I am also working against social norms, attitudes, and beliefs about eating animals that have been socialized and deeply embedded in my students since birth. Kathryn Gillespie (2018) described the experience of repeatedly witnessing violence against animals while others remain apathetic as being “marked by profound loneliness and by feelings of madness” (p.79)—a perfect description of my post-discussion feelings. After several semesters of the same experience, I find myself questioning my own competence as a professor.

All of this has led me to think more deeply about the key question in vegan sociology: what leads people to adopt veganism? I believe that just as eating animals is not natural, but rather learned through thousands of social interactions, veganism is learned over time through multiple interactions: a documentary, a positive animal interaction, a vegan meal, and yes—a book and a question. Even though the immediate discussion may not show it, and it can feel absolutely lonely and maddening, I believe this class session helps shift students a tiny bit closer to developing their sociological imagination and questioning things they have taken for granted, including eating animals.

References

Bazterrica, Agustina. 2020. Tender is the Flesh. Translated by Sarah Moses. New York, NY: Scribner.

Gillespie, Kathryn. 2018. “The Loneliness and Madness of Witnessing: Reflections from a Vegan Feminist Killjoy.” Pp. 76-85 in Animaladies, edited by L. Gruen and F. Probyn-Rapsey. New York, NY: Bloomsbury.