By Alice Poma and Tommaso Gravante

Challenging the hegemonic (capitalist, colonialist, patriarchal, and speciesist) culture is an integral part of building a new world, and one way to do so is questioning our individual and collective emotions.

Our project focuses on the idea of a prefigurative emotion culture which would be the set of feeling rules activists consider appropriate for the new world we/they want to create. In other words, a prefigurative emotion culture is the attempt to feel the new world we aspire to, before reaching it.

Why a prefigurative emotion culture matters

A prefigurative emotion culture is not created through formulas, self-help books, coaching, or mindfulness, but collectively, through dialogue and reflection on what we should feel, and our counter hegemonic feeling rules differ from the dominant ones.

In a society where emotions are confined to the individual sphere (and still, for some, seen as irrational), where there is no emotional education and emotions are only addressed when they become a mental health issue, it’s understandable that we find it difficult to express and work on them collectively. However, if we don’t break through these barriers, we condemn ourselves to accepting—or suffering under—the dominant emotion culture.

All efforts aimed at building an emotion culture as part of social movement activities should not be seen as tacky, superficial, or reserved for more sensitive people. Following Hochschild: “Not simply the evocation of emotion but laws governing it can become, in varying degrees, the arena of political struggle” (1979: 568).

A few examples of prefigurative feeling rules in Mexican anti-system activism

Two feeling rules of the current capitalist system are: feeling indifference toward the collective and resignation in the face of building alternatives to capitalism (Poma, 2025)[1]. Starting from here, a prefigurative feeling rule observed in different social movements is caring about the common good and wellbeing.

A second rule that is common in many forms of struggle is not to resign oneself in the face of the difficulties and triumphs of the domination system. Resignation is a mood that we made from experience; therefore, to avoid it, it’s necessary to share stories that show that it’s worth continuing the fight. It’s important to keep in mind that resignation shouldn’t be confused with the need to rest or take a break from activism.

A third prefigurative feeling rule, is the need to feel a radical and constructive hope, defined as the hope that there is still much to save, and that we can only achieve it collectively.

How can this other emotion culture be consolidated?

To consolidate a prefigurative emotion culture we need to recognize whether we have succeeded in establishing new feeling rules that we share with other groups, collectives, communities, and so on. For instance, if love for all animals is not only something that characterizes us as individuals but also something we believe we should feel—or that it’s right to feel— and that we share with other people and groups, we can consider this emotion a feeling rule. Starting from that point, we can then evoke, share, and spread it so that it becomes a feeling rule shared by more people and groups, as happens, for instance, in the LGBTQAI+ community where pride becomes a counter-hegemonic feeling rule to overcome the shame that many societies impose on those who are not heterosexual.

The best path to strengthen a prefigurative emotion culture is through empathy, which helps us accept differences (not only ideological or belief-based, but also in how we construct emotions). As Hochschild (2016) showed, imposing a rule can generate resentment in those who don’t share it.

Conclusions

Observing which emotions activists believe they should ideally feel allows us to glimpse, in a prefigurative way, the new world we aspire to, which, as the Zapatistas imagine can be “A world where everyone is who they are, without shame, without being persecuted, mutilated, imprisoned, murdered, marginalized, oppressed” (2023)[2].

References

Hochschild, A. R. (1979). Emotion Work, Feeling Rules, and Social Structure. American Journal of Sociology, 85 (3).

Hochschild, A. R. (2016). Strangers in their own land: Anger and mourning on the American right. New Press.

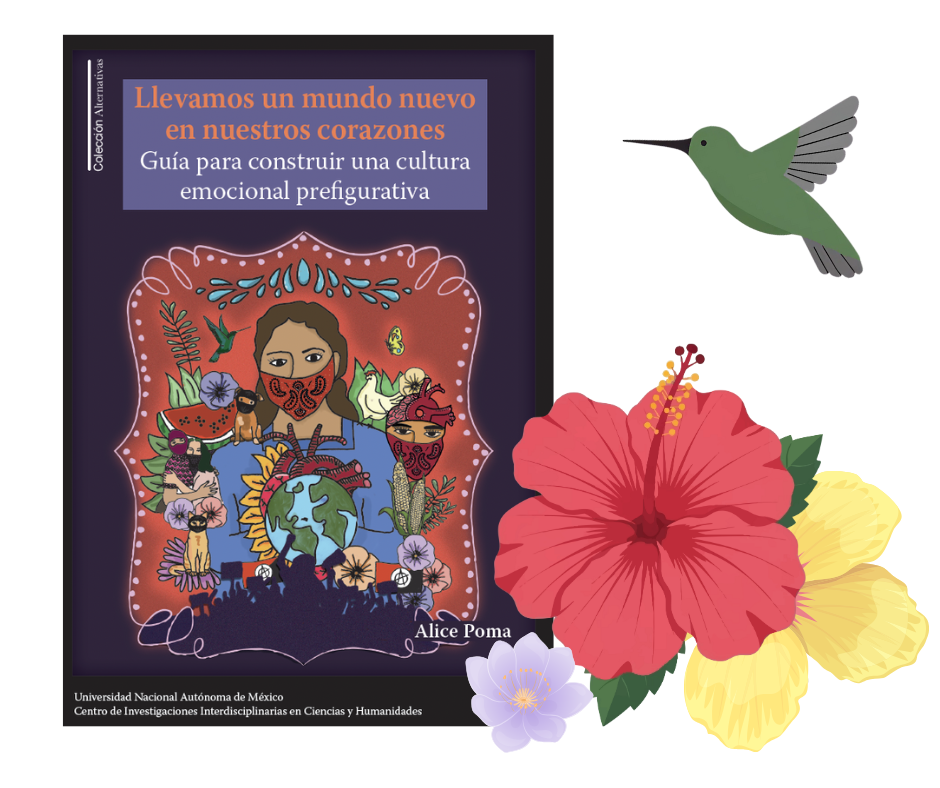

Poma, Alice (2025). Llevamos un mundo nuevo en nuestros corazones. Guía para construir una cultura emocional prefigurativa. Mexico City: CEIICH-UNAM.

Notes

[1] The Emotional Culture of Capitalism a conference by Hochschild, available here: https://fb.watch/ncgm9_COkP/

[2] https://enlacezapatista.ezln.org.mx/2023/11/22/twelfth-part-fragments-fragments-of-a-letter-written-by-subcommander-insurgent-moises-sent-a-few-months-ago-to-a-geography-distant-in-space-but-close-in-thought/